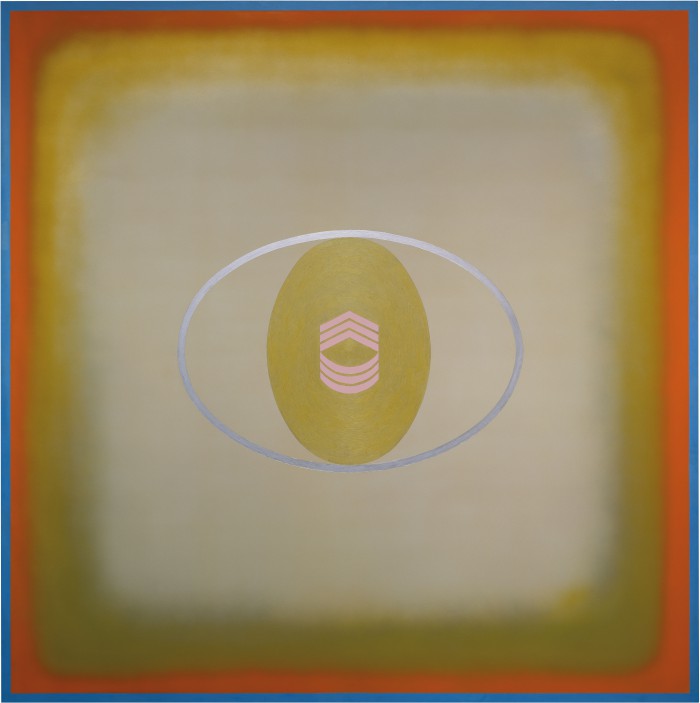

Billy Al Bengston

Lux Lovely 1962

Reproduction of this image, including downloading, is prohibited.

Welcome to the Anderson Collection

Stanford University's free museum of modern and contemporary American art

Reproduction of this image, including downloading, is prohibited.