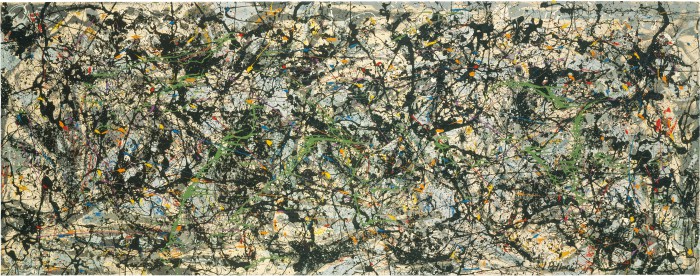

Jackson Pollock

Lucifer 1947

© 2014 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Reproduction, including downloading of ARS member works is prohibited by copyright laws and international conventions without the express written permission of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In a 1951 radio interview Pollock proclaimed: “It seems to me that the modern painter cannot express this age, the airplane, the atom bomb, the radio, in the old forms of the Renaissance or any other past culture. Each age finds its own technique.” Lucifer is among the earliest examples of Pollock’s own groundbreaking approach, which involved dripping, pouring, and splattering paint directly onto a canvas that had been tacked to the floor. The painting signals its modernity through Pollock’s choice of black enamel and aluminum paints, materials traditionally reserved for industrial use. A dense network of paint covers the entire surface of the canvas, creating an “all-over” composition. The bursts of yellow, red, orange, blue, and purple were squeezed directly from paint tubes. Pollock then propped the canvas on its side to add the final color, green; the resulting horizontal drips emphasize the painting’s panoramic dimensions.

Pollock gave Lucifer to Grant Mark, a chemist whom he began seeing in 1952 for his alcoholism, as payment for his services. Referring both to the morning star (which in Latin is called lux ferre, or light bringing) and the fallen angel by that name, the title Lucifer poignantly suggests an endless fall into the depths of the picture and the artist’s psyche.

-Sidney Simon, PhD ‘18

“There was a reviewer a while back who wrote that my pictures didn’t have a beginning or any end,” Jackson Pollock once recalled. “He didn’t mean it as a compliment, but it was. It was a fine complement.” By dripping, pouring, and splattering paint onto the surface of a canvas tacked carefully to the ground, Pollock constructed not just an anti-narrative picture but one that was radically open, existing perpetually in static suspension. Lucifer represents one of Pollock’s earliest experiments with his method of “action painting,” which created “all-over” compositions. While Pollock’s of-the-moment style surely evoked the chaotic industrialization of the immediate postwar period, reviewers tended to focus on the artist’s life and mind. Hans Namuth’s 1950 photographs of Pollock in the act of painting give us a beginning and an end: we see Pollock in action but also glimpse hints of his troubled psyche. Traded with chemist Grant Mark, for health services, Lucifer paralleled the titular angel’s fall from grace with the artist’s own regressions into alcoholism.

-Christian Whitworth, PhD candidate in the Department of Art & Art History

From Left of Center, opened Sept 20, 2019

Friendships in the New York School

By dripping, pouring, and splattering paint onto the surface of a canvas for Lucifer, Pollock constructed not just an anti-narrative picture but one that was radically open. Creating all-over compositions surely inspired by the chaotic industrialization of the post-war period, he changed the course of Abstract Expressionism profoundly. Deriving inspiration from the titular angel’s fall from grace, Pollock provides viewers with a glimpse of his own psyche. By embracing spontaneity, physicality, and the subconscious, Pollock’s art becomes a direct reflection of the creative spirit of his time.

Pollock’s work is a testament to the transformative power of artistic collaboration and interchange. He was in a constant exchange of ideas with fellow members of the New York School. His action painting technique was influenced by Franz Kline’s bold, gestural marks and emphasis on strong, contrasting forms. Philip Guston’s shift from abstraction to figuration during the 1960s motivated Pollock to question the boundaries of representation. William de Kooning’s innovative approach to figurative representation challenged Pollock to confront the tensions between abstraction and representation. The reciprocal nature of influence is also significant, as Pollock’s radical artistic vision profoundly affected these artists in return.

—Irmak Ersoz ‘24