Reviews

Stephanie Syjuco: White Balance/Color Cast | Anderson Collection at Stanford University

BY Rachel Heise Bolten, January 3, 2023

Stephanie Syjuco’s exhibition White Balance/Color Cast, on view through March 5, manufactures histories, real and counterfeit. Her work includes photographs, though she does not call herself a photographer – she teaches sculpture as an associate professor at the University of California at Berkeley. Her pictures feel crafted, made. For Hard Light and Neutral Orchids, Syjuco covered living flowers with paint and then photographed them, grocery-store specimens turned grey and white, orange tulips that cast a neon light. Pictured suspended before death, the orchids lived for a few weeks after painting, some even blooming a little.

These and other works play with processes of digital alteration. In Hard Light (the title refers to a Photoshop filter), white lilies are set against the checkered backdrop of a transparency layer. The subject of Chromakey Aftermath is an arrangement of protest leftovers (flags, barriers, bricks), colored green-screen green, blank for superimposition. Color-calibration charts show up throughout the exhibition: as objects, they have a pop appeal, grids of cyan and yellow and magenta. Used to check and adjust color, they center whiteness in our sense of what makes a picture correct or true.

Rogue States, the first thing you see inside the museum, includes flags suspended from the ceiling in rows that turn the atrium into a hall of nations, except that these represent not actual countries but terrorist states from Hollywood movies. Cargo Cults makes fiction out of ethnographic photography, colonial fantasies of national dress with belts and leggings from H&M, Target, and the Gap. Syjuco bought the clothes with her credit card and later returned them. In the portraits you see tags still attached, hanging signifiers.

Stephanie Syjuco, Cargo Cults: Head Bundle (Small), 2016. Courtesy the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, and RYAN LEE Gallery

In 2019 Syjuco spent two weeks at the Missouri Historical Society looking for photographs of the Philippine Village at the 1904 World’s Fair. Block Out the Sun is set apart from the main show, down a short hallway, but the click that punctuates each new photograph in the video sounds throughout the gallery. (An earlier version of this piece featured photographs in a vitrine, but here it takes the form of a slideshow.) This is an invitation to come see, but an ambivalent one. Syjuco’s hands cover the faces of the men and women brought to St. Louis as a human attraction, giving brief privacy from the imperial gaze.

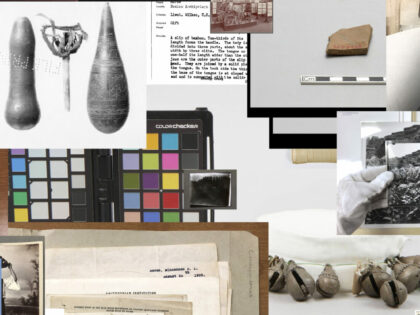

Three pieces from Pileups anchor the show. Made while Syjuco was a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellow in 2020, these capture the strange thrill of the archive: assemblages of plant specimens, identification cards, letters, portraits, ceramic fragments photographed or copied and layered together. Here is the hand of the artist again, white-gloved, placing and arranging. In the bottom left corner of Brass Bells, a group of white men and women are pictured with coffins and human skulls, the photograph layered over another of a beaded necklace against a blue backdrop, a partial view of a person posed in landscape, and a typewritten note, mostly obscured, which reads in part, Taken from the body of the brother.

Eastman includes a photographic portrait Syjuco found in the anthropology collection at the National Museum of American History, labeled “Man?” The artist, who was born in Manila and came to the United States at the age of three, knew him right away: national hero José Rizal, intellectual and political activist. When is an archive a form of erasure? See yourself reflected in the glass frame. Keep looking.