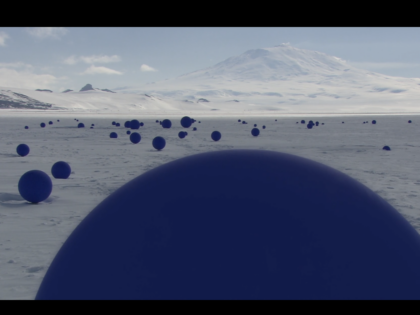

Stepping into the Wisch Family Gallery at the Anderson Collection at Stanford University evokes a polar desert’s quiet and dangerous beauty. Centered amidst large-scale photographs of a pristine white, icy environment, an otherworldly ultramarine-blue sphere measuring slightly over 3 feet in diameter rests on a bed of what appears to be snow. The sphere, representing Rigil Kentaurus, the third-brightest star in the night sky, is a key element of an immersive exhibition titled Stellar Axis on view through Aug. 18.

In 2006, California-based environmental artist Lita Albuquerque led an expedition to the farthest reaches of Antarctica near the South Pole to create Stellar Axis: Antarctica. The journey to the ice included a team of experts, researchers, and artists, with Albuquerque at the helm. Their sole purpose was to create a sculpture and ephemeral event on an unprecedented scale and in a completely unprecedented location.

The expedition was aided by a grant from the National Science Foundation and was the first and largest ephemeral artwork created on the continent. The resulting installation consisted of an array of 99 fabricated blue spheres where each sphere’s placement corresponded to the location of one of 99 specific stars in the Antarctic sky above, creating an earthly constellation at the South Pole. As the planet rotated and followed its orbit around the sun, the displacement between the original positions of the stars and the spheres drew an invisible spiral of Earth’s spinning motion.

Since the early 1970s, Albuquerque has created an expansive body of work, ranging from sculpture, poetry, painting, and multimedia performance to ambitious site-specific ephemeral projects in remote locations around the globe. Often associated with the Light and Space and Land Art movements, Albuquerque has developed a unique visual and conceptual vocabulary using Earth, color, the body, motion, and time to illuminate identity as part of the universal.

For Albuquerque’s exhibition at the Anderson Collection, one of the surviving 99 spheres is on view amid a bed of salt, standing in for snow. It is accompanied by a selection of photographic works of the Antarctica installation by polar historian and artist Jean de Pomereu, a meditative 8-minute video of the ephemeral artwork by Lionel Cousin, and one painting from Albuquerque’s Auric Field series.

“We’re at a moment in history where it’s essential to find universal points of human connection, and art and artists are a vehicle for doing that,” said Jason Linetzky, director of the Anderson Collection. “Lita Albuquerque considers this installation at the Anderson a carefully composed painting, serving to turn our attention to the interrelatedness and bond all humans have to Earth and the cosmos.”

The museum’s first floor houses an intimate gallery space where de Pomereu’s large-scale photographs and a video projection with a soundtrack by Jon Ray enhance the immersive experience. The inclusion of the luminous Auric Field painting and excerpts from Albuquerque’s diaries, such as the following two written during the artist’s time in the Antarctic, serve to tie the elements of the exhibition together:

When I close my eyes I see entire planets covered in ultramarine blue pigment, I see our planet from outside our solar system, as a part of a vast circulatory system of stars, and in Stellar Axis, the planet cradled by both poles.

On the ice, the palpability of our interdependence and interconnection is magnified and brings us back to our humanity, to our human life and to the fragility of our human experience.

In 2014, the Nevada Museum of Art, Center for Art + Environment, home to Albuquerque’s Stellar Axis archive, organized an exhibition and published a major monograph of the work, available at the Anderson Collection. In addition to essays placing the artist’s works in the broader contexts of environmental art and science, Albuquerque provides personal reflections on her life’s work.

She will deliver the annual Burt and Deedee McMurtry Lecture at Stanford on April 24.