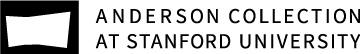

Robert Arneson

Sinking Brick Plates 1969

Art © Estate of Robert Arneson/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Reproduction of this image, including downloading, is prohibited.

Audio Description (02:36)

Full Audio Transcript (Expand)

Sinking Brick Plates

Robert Arneson’s Sinking Brick Plates from 1969 is a whimsical installation of five beige oval ceramic dinner plates in a line. The title perhaps builds an expectation of viewing plates made of brick that are sinking. Rather, they look like water-filled plates made especially for sinking a brick, a delightfully implausible idea, as a brick is much too thick to sink into the shallow water that a plate could hold.

The bricks in this work are not real bricks, but dark red clay replicas. Where the manufacturer’s name would have been stamped into the clay along one long side, these instead say simply, “Brick.” Otherwise, the bricks are realistic with smooth, dull faces, and edges that are slightly cracked or dented in places. The plates are subtly uneven, ranging in size from around four by nineteen inches down to one-and-a-half by eighteen-and-a-half inches. Their beige coloring is variable and uneven, and the final glaze over the plates shimmers like glass.

Arneson deftly executes his joke of sinking a brick on a plate by filling each dish with brightly glazed clay colored with swirling blue, teal, and dark green pigments. The unevenness of the blues and greens creates a representation of a natural body of water, whose colors change depending on depth, plant life below or algae on top, and light hitting it differently as it waves.

In the first plate, a brick lies mostly flat, tilted gently to the left. Its top face with “Brick” stamped on it is still fully above water. The bottom left corner is beginning to sink first. The blue-green clay has been pinched into little peaks that hug the edges of the brick, as if the brick was just dropped in, and the parted water has sloshed back toward the brick to begin consuming it. In the second plate, the brick is still angled down on the left, and nearly one third of its left side is swallowed up. The pinched peaks of clay rise higher, the miniature waves cresting. The third plate reveals the brick more than three-quarters sunk, and it is now nearly vertical. The water around it peaks higher, and circles of the disturbed water radiate out toward the edges of the plate. In the fourth, the plate’s dish is full of ripples along the water’s surface, and only one corner of the brick is left peeking out, a tiny clay pyramid. In the fifth and final plate, the water has completed its meal. The only evidence the brick was ever there is the rising and falling of the water’s ripples in imperfect circles taller at the plate’s center and becoming gentler toward the edges.