“How did they fit all this art in their house?” That was the question of the day at the media preview for Stanford’s new Anderson Collection, which opens to the public with a grand celebration this Sunday, September 21.

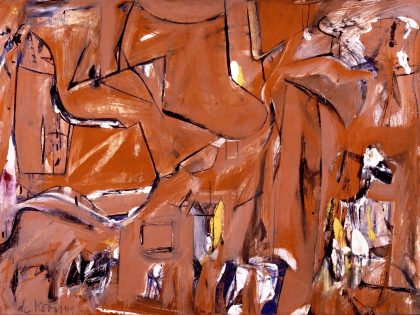

Being surrounded by museum-quality works by artists including Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock and Richard Diebenkorn was a way of life for collectors Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson, but it was a tight fit. Imagine having an Alexander Calder mobile in your living room, a Hans Hoffman color-saturated landscape over your bed.

Now, a portion of the Andersons’ blue-chip collection has a new and spacious home on the Stanford campus: a beautiful bespoke museum designed to showcase the Modern and contemporary American paintings and sculptures the couple has so carefully acquired over the last 50 years. Richard Olcott of Ennead Architects designed the 30,000-square foot building, which was completed in May (the last four months have been spent delivering and installing the art) and constitutes another glittering jewel in the crown of the burgeoning campus arts district.

From private to public

The museum houses 121 works of art by 86 artists, a gift to the university from the Andersons (affectionately known as Hunk and Moo) and their daughter, Mary Patricia Anderson Pence. The history of their collecting is by now the stuff of legend: After a trip to Europe in the 1960s, Hunk and Moo decided to educate themselves about art in order to build a collection. They sought out the best examples by the most noteworthy artists available, and had the good fortune — and foresight — to purchase stellar works by artists working in the Abstract Expressionist movement before prices became prohibitive. Their collection grew, filled their ranch house in Atherton and then became part of the Saga Food headquarters (now Quadrus) on Sand Hill Road; Hunk was a co-founder. Along the way, Hunk and Moo were always intent on sharing the collection and educating the public about contemporary art — not always an easy sell, especially given their proclivity for abstract works.

After years of active collecting in schools as wide-ranging as California Funk, Color Field Painting and Bay Area Figurative Art, the Andersons decided to begin gifting their collection to museums. Though they were courted by collections across the country, the couple preferred to keep their focus local, making gifts to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

“Our interest is to support the arts in the Bay Area,” explained Hunk in a phone conversation last week. “We believe that art enhances the human experience, and this museum is a gift that keeps on giving.”

Informal, casual and accessible

The opening of the Anderson Collection at Stanford University marks the first time the public has had access to such a wide range of these works in one place. It’s an unprecedented experience. Upon entering the lobby of the building, the viewer first encounters two colorful, playful sculptures by California-based artists Charles Arnoldi (“Untitled I,” 1983) and Robert Hudson (“Plumb Bob” 1982). They are fun and lively, and perhaps lead the visitor to think that all the mystery about modern art is exaggerated. But then the grand staircase, which takes the visitor to the second floor where the majority of the art is installed, leads directly to an encounter with Clyfford Still’s “1957-J No.1.”

The work is an interesting choice for such a focal point; large in scale, with only three colors of paint (red, black, white) applied thickly with a palette knife. Its jagged forms and bold composition are confrontational and somewhat unsettling. Look to the left, however, and the eye takes in the cheerful swirls and bright pastels that comprise Joan Mitchell’s “Before, Again IV.” Gaze right, and Richard Diebenkorn’s evocative seascape, “Ocean Park #60,” immediately produces a sense of calm and tranquility.

This is the charm, as well as the secret, behind this museum. Rather than an encyclopedic gathering of art from every modern movement since 1945, this is a personal collection that reflects the taste and priorities of the Andersons. Hunk, who feels that art collectors are really just “stewards,” refers to the works the family has amassed as a “collection of collections,” acknowledging the couple’s broad rather than narrow interests, their eye for artistic innovation as much as anything.

Since the collection is idiosyncratic and personal, explained architect Olcott, he focused his design for the museum on three goals: “informality, casualness and accessibility.” The museum, he says, “reflects the way the Andersons lived with art in their ranch-style home.” To that end, the floor plan is open, eschewing small rooms. Visitors can wander freely, without directives based on chronology or strict groupings of works. And, just as the Andersons mixed Rodin sculptures and early American antiques with modern art in their home, the visitor finds unexpected juxtapositions in each viewing space.

Consider the area dedicated to Geometric Abstraction, for example. Ad Reinhardt’s exquisitely subtle black-on-black study “Abstract Painting 1966” is hung next to the screamingly bold yellow “Homage to the Square: Diffused, 1969” by Josef Albers. In the same room is Ellsworth Kelly’s “Black Ripe, 1955,” consisting of a large, black amoeba-shaped form that seems trapped inside the confines of the canvas. Among all these non-objective paintings stands a lovely and delicately crafted female torso entitled “Largo-May,” executed in copper and steel, by Saul Baizerman. Somehow, it works.

Looking at a legacy

It is these unpredictable combinations that distinguish the Anderson Collection from most museums. There are explanatory labels that provide the public with more in-depth art historical information, but, for the most part, viewers are encouraged to just use their eyes. One can move from space to space, weaving in and around the open hallways which were designed to mimic the campus’s traditional pedestrian arcade, or sit on one of the strategically-placed benches and engage with just one work of art. There is plenty of room for each and every object, and diffused natural lighting illuminates without being jarring.

A review of the new museum would not be complete without mentioning a key piece from the Anderson collection: “Lucifer” 1947 by Jackson Pollock. One of the last works by the famed artist that remains in a private collection, “Lucifer” would be welcome in any museum in the world. It is a superb example of Pollock’s drip technique, and a vibrant dance of color and gesture. While it once hung in the Andersons’ dining room, it now enjoys a prime spot in the museum’s Abstract Expressionist space, along with other important works from the movement by Mark Rothko, Franz Kline, David Smith and Robert Motherwell.

Although the current installation includes 104 pieces from the gift, museum director Jason Linetzky noted, “There will be opportunities to bring in additional works from the original gift. Visitors will see how the experience changes when works are rotated.”

A temporary exhibition space on the first floor features the work of the late Leo Holub, who founded Stanford’s photography program in 1969. Holub was hired by the Andersons to take photographs of many of the artists represented in their collection. The black-and-white portraits, many of them taken in the artists’ studios, took ten years to complete. Together, they stand as a visual reminder that creating art is a distinctly human endeavor.

The Anderson collection and its archive will be an invaluable resource to Stanford students, especially now that each freshman is required to take one course in what the university calls “creative expression.” According to Matthew Tiews, Stanford’s Executive Director of Arts Programs, the requirement is “the University’s way of recognizing that the arts are fundamental to life.”

In the unlikely event that one tires of looking at the riches of the Anderson Collection, a wall of windows beside the grand staircase provides a view of the Cantor Arts Center (formerly the Stanford Museum of Art) as well as Richard Serra’s monumental sculpture, “Sequence,” installed on the lawn between the two museums. The sculpture, on loan from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, is an interesting bridge between the old museum — founded as a tribute to Leland Stanford Junior — and the Anderson Collection, a tribute to the artistic passion and dedication of the Anderson family. Once accessible to a select few, the Anderson Collection is now free and available to us all. That is a gift that keeps on giving.

Freelance writer Sheryl Nonnenberg served as a curatorial associate at the Anderson Collection from 1994-1999. She can be emailed at nonnenberg@aol.com.

What: Anderson Collection opening

Where: The Anderson Collection, 314 Lomita Drive, Stanford

When: 10 a.m. to 7 p.m.

Cost: Free, but timed tickets are required for admission

Info: Go to anderson.stanford.edu, call 650-721-6055, or email andersoncollection@stanford.edu.