Among the 121 major pieces of postwar American art he has given to Stanford, Harry W. “Hunk” Anderson has bled for just one — Frank Stella’s “Zeltweg,” a heavy, nine-piece, mixed-media painting that resembles a kids’ slot car track.

So when it arrives by heavy Freightliner on a mid-August morning, Anderson and his wife, Mary Margaret (Hunk and Moo, as they are known to just about everyone who has ever met them), come by to see its installation and note its symbolism as the last big artwork to take its place in the Anderson Collection at Stanford University.

“Well, what do you think?” Hunk says, while getting his first look at the walls nearly covered in his art. In terms of a single donation to open a museum on a prestigious college campus in a major metropolitan area, the Anderson Collection might be the most important opening since the Trumbull Gallery at Yale opened in 1839. In the West, the only thing that comes close is the Hammer Museum, which was open four years before being annexed by UCLA in 1994.

‘Unquestionably world class’

“The Anderson Collection is absolutely, unquestionably world class,” says Jeffrey Fraenkel of Fraenkel Gallery, the prominent San Francisco dealer in photography, a genre not included in the Anderson Collection. “Museums all over the country had their eyes on it hoping to get it until Hunk and Moo made their decision in favor of Stanford.”

The Andersons did not choose Stanford because they went there. They didn’t, and neither did their only child, Mary Patricia “Putter” Anderson Pence. Hunk attended Hobart College in New York, where he co-founded a company to manage the school’s cafeteria. He then came West to establish Saga in Menlo Park, a national company distributing dorm food to college campuses across the United States.

Museums far and wide courted the Andersons, but, logically, the art collection paid for by college cafeteria food belongs on a college campus. The deal, struck in 2011, was that Stanford would supply a new building, at a cost of $36 million, to be run independently of the neighboring Cantor Arts Center. The Andersons would supply the art, which has been scattered between Quadrus, their private showroom in Menlo Park, and their home in Atherton, where it has always been rumored that Putter slept beneath the last Jackson Pollock drip painting in private hands.

“We’re taking 60 works from the house and about 60 works from Quadrus,” Anderson says, raising the question of whether Quadrus will now be closed and the walls of his home will now be bare. “Even now, with the gift, we still have 700 works left,” he says. “But they’re not the irreplaceables. The irreplaceables are here (at Stanford).”

The irreplaceables

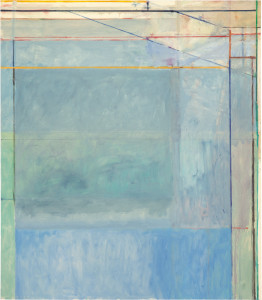

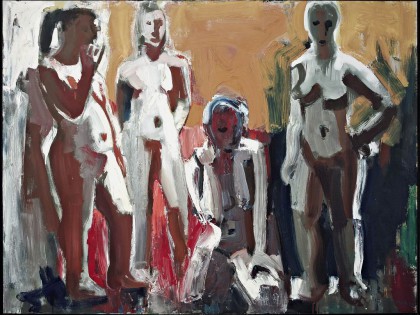

The irreplaceables include work by Jackson Pollock, Richard Diebenkorn, Wayne Thiebaud, and the Frank Stella now coming up the elevator in a wooden crate.

The “Zeltweg” story is indicative of how the Andersons built their collection. As Hunk tells it, the acquisition began with a doubles match at the Menlo Circus Club in Atherton. Stella and San Francisco art dealer John Berggruen were the guests and opponents of Hunk and Putter.

After the match, Stella invited the Andersons to a showing of his work, in 1981. They flew to New York and were driven to Stella’s studio in Lower Manhattan by Leo Castelli, the famed art dealer, who represented Stella. Also there for the showing were Donald Marron, a New York financier-collector, and Philip Johnson, founder of the architecture department at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The rules, as dictated by Castelli, were that Johnson got first choice and Anderson second choice. “I said, ‘Leo, you are putting me in an awkward position,’ and he just ignored me,” recalls Anderson, who could not conceal which one he wanted. Johnson deferred to him by making a different selection, leaving “Zeltweg” to Anderson. It was probably a six-figure purchase, even 33 years ago.

“I think this was Philip’s first choice,” Anderson says of “Zeltweg.” Named for a Formula One racetrack in Austria, the painting is on honeycombed aluminum. “A map of the experience of the track” is how Stella described it.

Records show that the work was publicly displayed during the opening of the new wing at the San Jose Museum of Art in 1992, and at an exhibition of the Anderson holdings at SFMOMA in 2000, but has not been out since.